Research Matters: Flooring And The Chain Of Infection

To use an evidence-based design process, you have to know what the best available evidence is. But research is published faster than anyone can read it. In this blog series, The Center for Health Design’s research team will provide insight into a few healthcare design research matters through a snapshot of 10 studies published since the 2016 Healthcare Design Expo & Conference. Serving as a sneak peek of an upcoming session at the 2017 HCD Expo, the blogs will identify why this research matters and help readers ride the waves of an ocean of research without drowning.

The research

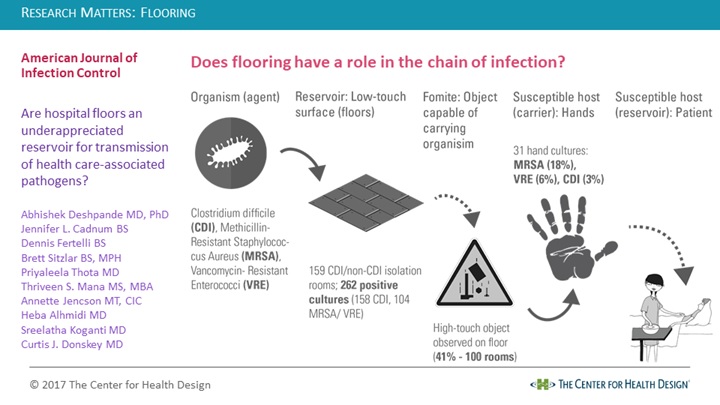

A 2017 “brief report” by Dr. Abhishek Deshpande and colleagues, who evaluated the frequency of Clostridium difficile (CDI), Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA), and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci (VRE) on isolation room floors and examined the potential for transfer from floors to hands.

Why does it matter?

Healthcare-associated infections are a burden to healthcare organizations and their patients on several fronts. A chain of infection is influenced by an organism (pathogen), a reservoir (host), and transmission events in which the organism leaves the reservoir and enters a new susceptible host, who can continue the chain as a new source of transmission (without developing an infection) or become a new host (if infected). Research on healthcare-associated infection has typically focused on the role of “high-touch” environmental surfaces such as bed rails or the bed surface and the need for improved hand hygiene compliance and disinfection during regular and terminal cleaning. While it has been acknowledged that hospital floors can be a source of contamination, conventional thinking is that floors aren’t an important source of infections, as they’re rarely touched. For example, early research on the topic describes contact transfers from hospital ward floors as a potential “sporadic” source of infection, and a 2001 study stated that infection risk from contaminated floors was small. However, a 2016 study traced noninfectious markers inoculated into a patient room floor and found the marker was rapidly transferred to hands and other high-touch surfaces both inside and outside the room. (CDI and MRSA are tracked as part of the current Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program.)

How was the study done?

The study was conducted in five U.S. hospitals without the knowledge of the hospital personnel. There were no changes in procedures or policies for cleaning associated with the study. When rooms were occupied, floors were only cleaned when visibly soiled and after discharge, using a quaternary ammonium-based disinfectant. (One facility also used a UV-C decontamination system.) Two 1-square-foot areas of the floor (near the bathroom and near the bed) in 47 CDI isolation rooms and 112 randomly selected non-CDI isolation rooms on the same unit were sampled with a culture swab. An adjacent 1-square-foot area was used to sample for CDI “broth enrichment cultures.” About 30 rooms in each facility were included in the sample. They were either occupied (109 rooms) or had just been cleaned following patient discharge (50 rooms). Cultures were processed for MRSA, VRE, and CDI. Additionally, researchers observed the number and type of high-touch objects on floors in randomly selected patient rooms in each facility (10-25 per hospital). The researchers picked up items they observed in direct contact with the floor (gloved or bare hands depending on room type). Their hands were cultured for pathogens (before and after, if bare).

What was learned?

Analysis of 318 floor samples revealed floor contamination was common in both room types. CDI was found most frequently, but MRSA and VRE were found significantly more often from floors in CDI isolation rooms than the non-CDI isolation rooms. The contamination was similar at all of the study sites in both bathroom and bed locations. Rooms cultured following occupancy and cleaning had statistically significantly less contamination with MRSA and VRE (but CDI prevalence was not significantly different from a statistical perspective). Of the randomly occupied rooms observed by researchers, there were between one and four high-touch objects (such as clothes, cell phone chargers, call buttons, blood pressure cuffs, bed linens, towels, etc.) in contact with the floor in 41 of 100 rooms. Culture analysis of the researchers’ hands associated with contact of these high-touch objects found recovery of MRSA in six of the 31 cultures, VRE in two and CDI in one.

Are the results definitive?

As with any study, there are limitations. Only three pathogens (albeit common ones) were investigated and additional research is needed for other types of pathogens and viruses. The study only looked at isolation rooms (CDI and non-CDI), and none of the five organizations used the sporicidal disinfectants more typically used on high-touch surfaces on their floors. Only one used a UV-enhanced cleaning protocol, which has been shown to reduce the frequency of positive cultures for the pathogens in this study. The study doesn’t provide a direct link between the prevalence of pathogens and patient-related outcomes of healthcare-associated infections, and the authors provide no detail about the flooring surface qualities or condition in each facility.

The takeaway

It’s almost like the five-second rule for food on the floor. In your home, you drop something on the floor and ask: Is it safe to eat? In the hospital: Do I need to wash my hands after picking this up? Organizations may sometimes feel flooring selection is more about falls, aesthetics, or durability, as flooring in healthcare hasn’t been empirically linked to infections. However, its classification as a low-touch surface may contribute to what the research team calls an “under-appreciation” of the role of flooring in transmission. Flooring selection in healthcare has been associated with evidence-based design goals related to patient and staff safety, noise, staff fatigue, surface contamination, the patient experience, indoor air quality, and return on investment. The study helps designers, infection preventionists, clinicians, and other stakeholders understand the chain of infection for low-touch surfaces, such as floors.

From a design perspective, flooring selection continues to be complex and needs to be considered in a larger context. A proactive approach is needed to include flooring selection as an interdisciplinary process that is considered in the context of organizational policies and procedures (such as cleaning protocols and infection control policies, and whether existing policies go far enough) and the behaviors and tasks of people using the space (such as where patients and families plug in electronic devices, where staff place clinical equipment and accessories, or the convenience of hand hygiene stations). Things end up on the floor when there is no place else to put them, and this may warrant additional design considerations outside of floor selection. There’s more to floors!

Interested in the topic? Visit The Center for Health Design Knowledge Repository for more. Ellen Taylor, PhD, AIA, MBA, EDAC, is vice president for research at The Center for Health Design. She can be reached at etaylor@healthdesign.org.

Summary of:

Deshpande, A., Cadnum, J. L., Fertelli, D., Sitzlar, B., Thota, P., Mana, T. S., … Donskey, C. J. (2017). Are hospital floors an underappreciated reservoir for transmission of health care-associated pathogens? American Journal of Infection Control, 45(3), 336–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.11.005